Students protest outside the UNI Administration building on April 21, 1970.1

Radical Times

The early years of the 1970s were marked by rising tension between marginalized portions of the student community and University administration. The drive among under-represented student groups was led by the Afro-American Society (AAS), which aimed to capitalize on wider trends of the Black Power and other social change movements taking place in the United States. Between the years of 1969 and 1971, one of the defining struggles for the AAS was the establishment of a cultural center for Black students and their allies.

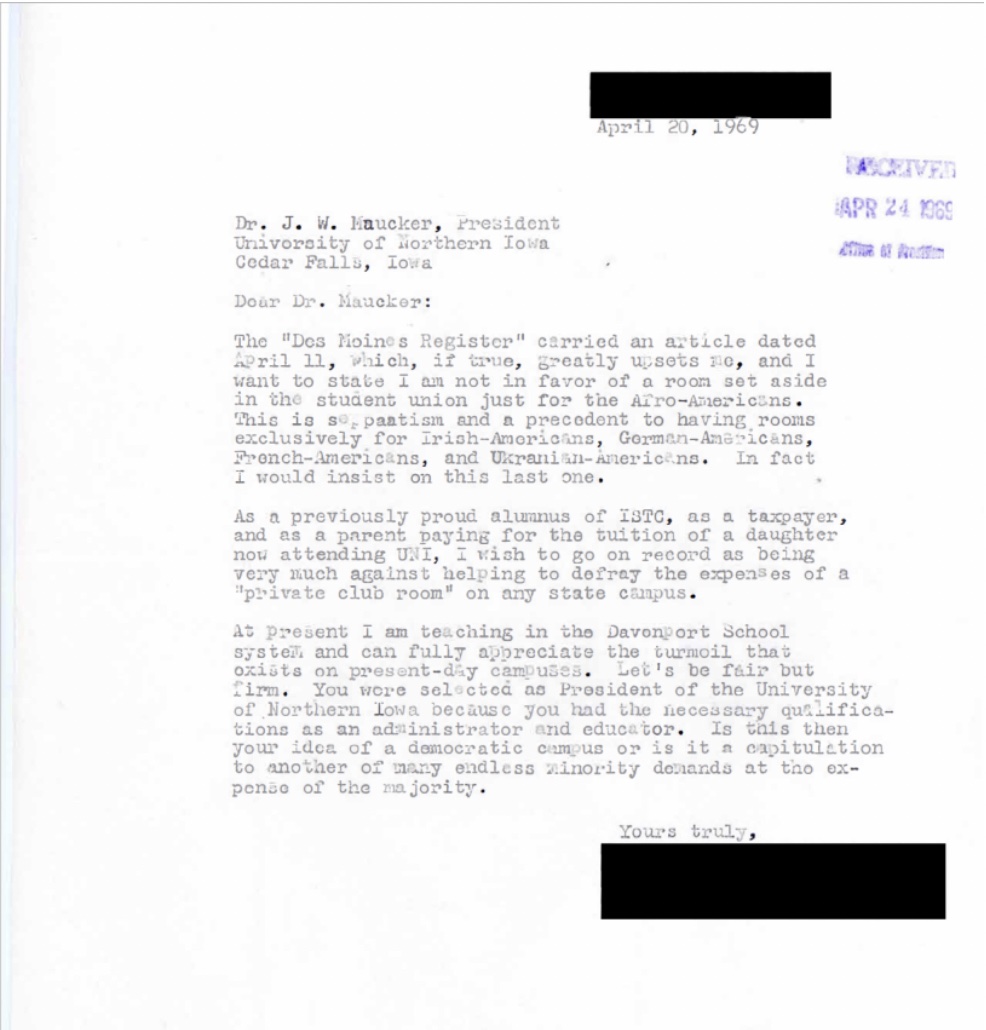

The issue was brought to the attention of the University along with the demands of the Society in 1969, but sparked major controversy early in 1970. Feeling that the University administration was deliberately stalling discussions regarding the cultural center, a group of students affiliated with the AAS went to President J.W. Maucker’s home on campus and staged a sit-in protest to demonstrate their dissatisfaction.

The sit-in lasted for two days in March of 1970 and sparked a wave of confrontations between students and University administration. In the month that followed, the university attempted to hold clandestine disciplinary hearings behind closed doors, a move which many members of the community saw as unjust. The series of protests that followed resulted in the arrests of nine student demonstrators and stern criticism of both Maucker and the student-faculty disciplinary committee he established. These events galvanized public opinion on ethnic relations on the UNI campus and served to set the tonal precedent for the subsequent years of the decade.

The EMCEC

The opening of the Ethnic Minorities Cultural Education Center (EMCEC) on Black History Week of 1971 marked a significant turning point in the operations of the Afro-American Society. For the remaining eight years of the 1970s and beyond, the EMCEC served to enhance the voice of marginalized ethnic groups via art, music, poetry, film, and speaking events. Many noteworthy guest speakers came to campus, such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Jesse Jackson, Ida Lewis, Maynard Jackson, and Maya Angelou. The EMCEC harnessed the sentiments of the Black identity to enhance the representation and voice of marginalized members of the community.

The prominent portrayal of Black identity became central to the mission of the Afro-American Society, which reformed into the Black Student Union (BSU) in October of 1972. The events sponsored and advocated by the BSU and the EMCEC helped give rise to important discussions on other controversial topics of the day, such as gender discrimination; the 1970s saw the establishment of two non-white dominated Greek Life organizations, both of which were the first of their kind at UNI.

The End of an Era

As the decade came to a close, there was a gradual but distinct shift away from the more radical message and ideology that dominated 1970 through 1972. The operations of the BSU and EMCEC pivoted to representations of diverse culture and educational outreach as the wider Black Power movement fizzled out across the nation. The history of the University of Northern Iowa during the 1970s can be seen as a microcosm of sentiments and events sweeping the nation in the wake of the 1960s, especially in regards to the ideas of Black Power and marginalized cultural identity. The Afro-American Society’s advocacy in the early years of the decade were focused around gaining recognition for black students on campus through demonstrations and demands designed to shake the foundations of an administrative system they viewed as corrupt. As the decade went on, the organization transitioned into advocating for cooperation and mutual understanding between groups rather than seeking out direct conflict. The efforts of the EMCEC to cultivate education regarding various marginalized groups also reflected the shift towards a less radical time.

Regents Approves Cultural Center

The Iowa State Board of Regents gives its approval for the establishment of a cultural center on the UNI campus, but stipulates that no public funding may be used for the project. The initial vote by the Board ended in a stalemate of 4-4 over the issue of using tax money for the construction of a center for a particular marginalized group. The subsequent 6-2 vote decided that the name must drop the words “Afro-American” as to not show favoritism to any one specific group of students.

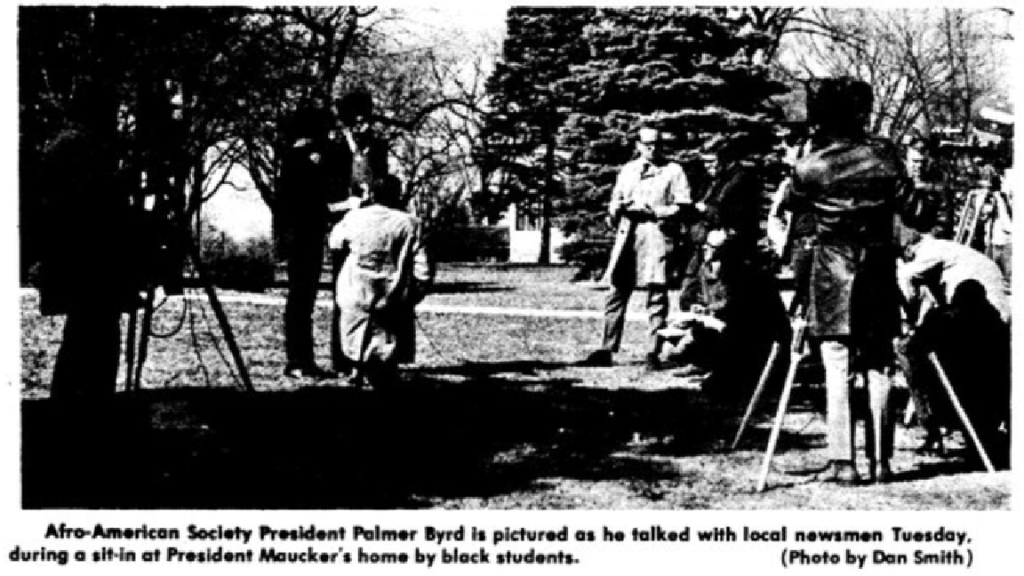

Sit-in at President Maucker’s Hause

Members of the AAS stage a sit-in in President Maucker’s house in protest of the University’s intransigence towards their requests regarding the proposed cultural center. The sit-in was organized over President Maucker’s refusal to commit to any written agreements regarding the demands of the Afro-American Society. When members of the AAS went to Maucker’s house and discussed the matter with him, they decided that they would remain in the home until a firm decision was made in writing. The President arranged for a campus security officer to watch the students while he and his wife slept, while UNI attorney Leo Baker

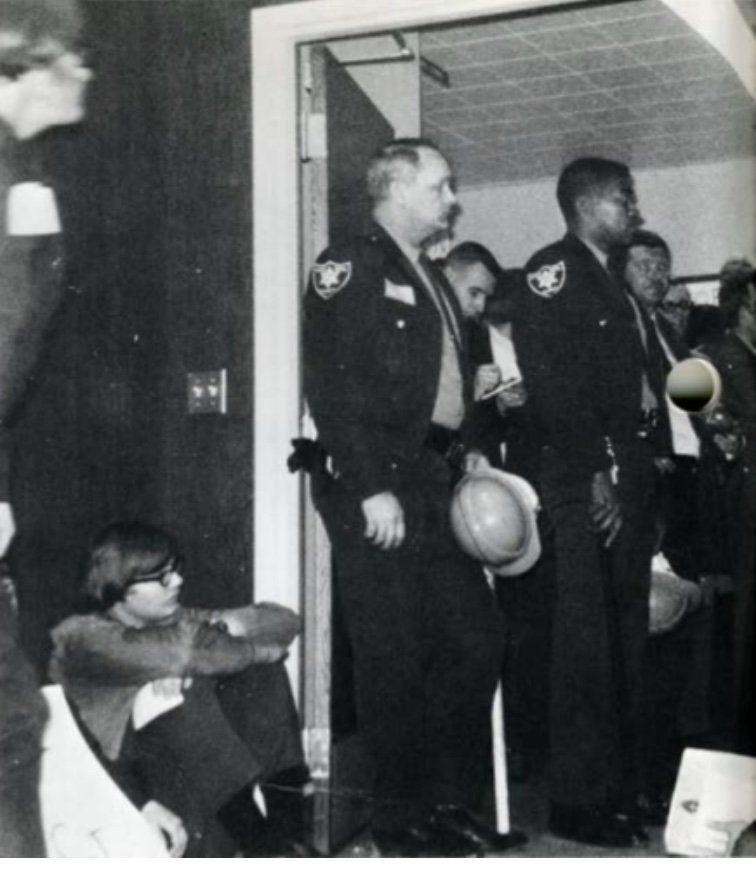

Students disrupt hearing

Ttudent advocates entered the room where the disciplinary hearing for AAS President Palmer Byrd was being held. Because of the disruption, Professor Keefe (Chairman of the University Senate) adjourned the meeting indefinitely.

Students arrested at hearing

, the student-faculty disciplinary committee attempted to begin the hearings for the UNI-8 but were interrupted when a student assembly entered the room in protest. Nine students were arrested for violating a Black Hawk County District Court order and were sent to the Black Hawk County Jail.

Maucker Denounces Sit-In Movement, Threatens Arrest

President Maucker made a statement that any “unauthorized” individuals who entered the Administration Building on campus while the hearings were being conducted would be issued injunctions and subjected to immediate arrest. Afterwards, a large protest marched to stage a sit-in of the hearings. 20 of these marchers were issued bench warrants and charged with contempt of court for violating a court injunction.

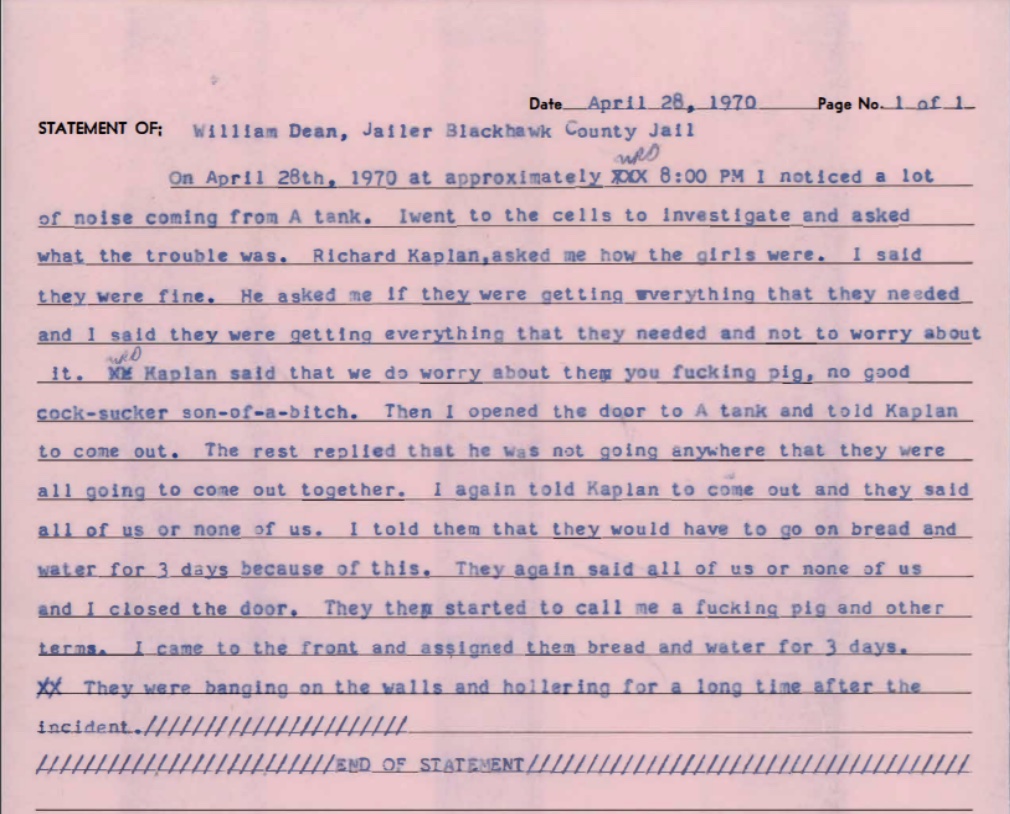

Black Hawk County Jail Abused Student Protestors

The Black Hawk County Jailor, William Dean, restricted the students in custody to bread and water for 3 days after Richard Kaplan reportedly used derogatory language in conversation with him. Kaplan reportedly inquired as to the condition of the female students in detention and when Dean told him not to worry about them, used profane language and insults.

Student Senate Demands the University Drop All Charges

The UNI Student Senate sent a recommendation to UNI Administration urging them to drop all charges against the defendants of the disciplinary hearings. They state in their list of reasons that the student-faculty disciplinary committee’s efforts “have proved inadequate to the task at hand” and that they “neither morally or legally will recognize double jeopardy as a means of punishment at the university.” They say that recent events made it impossible to hold a fair hearing for anyone in the current political climate on campus.

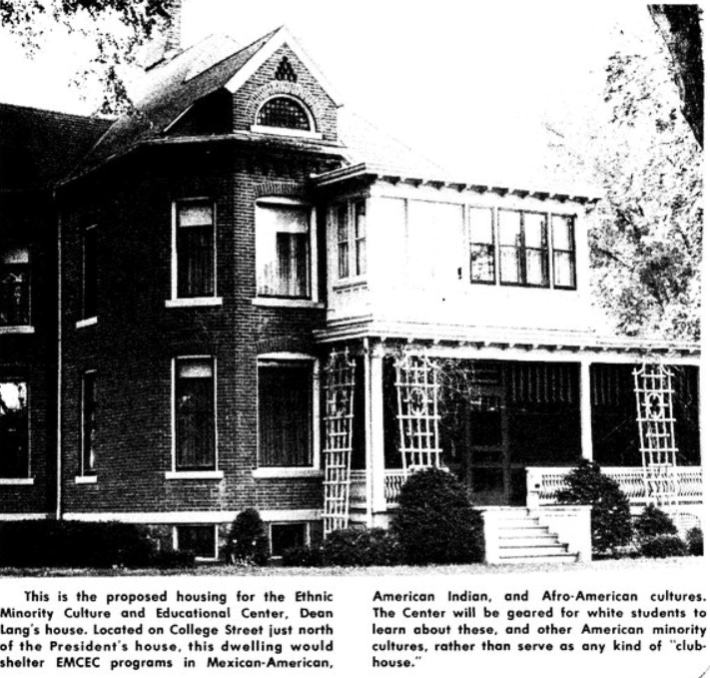

Board of Regents Approved Plan for the EMCEC

The State Board of Regents approved the establishment of the EMCEC in the former residence of Dean Lang after an extensive fundraising campaign by members of the campus and local communities. An agreement was reached stating that the University would provide the funding necessary for the maintenance of the center and its utilities.

EMCEC Hosts its First Black History Week

The opening of the EMCEC is scheduled to take place during the week of the 7th through the 13th with highlights such as the presentation of original African painting and sculpture by Betty Hooper and a speech by Rudolph Windsor (director of the Afro-Israelite Cultural Center in Philadelphia) on “The Ancient Blacks in the Middle East, Manifesting Their Relationship to the Current Arab-Israeli Crisis.”

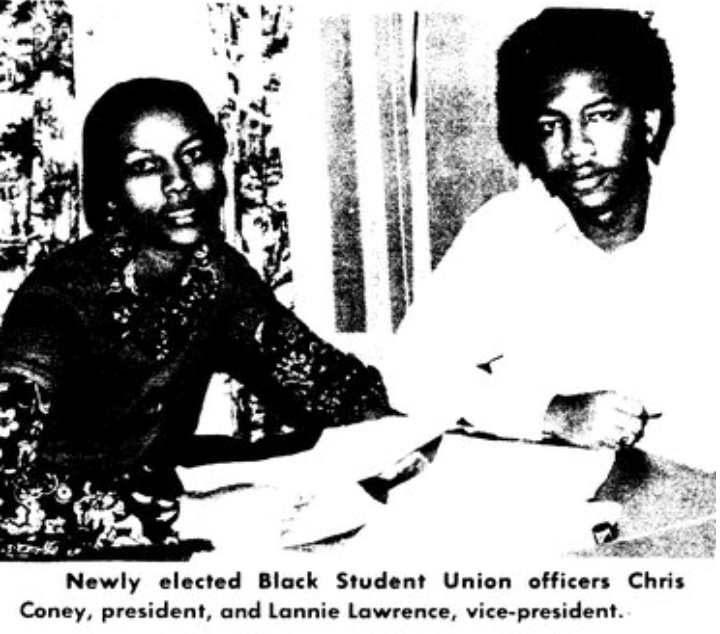

Afro-American Society Becomes the Black Student Union

The Afro-American Society reformed into the Black Student Union under the new leadership of elected president and vice-president Chris Coney and Lannie Lawrence, respectively.

UNI Students Engage with Prison Reform

Inmates from the Anamosa State Reformatory join the Black History Week lecture series to discuss prison life and present programs on Black culture. EMCEC Director Abram Emerson states that “the observance of Black History Week is to teach members of the University and the Metropolitan

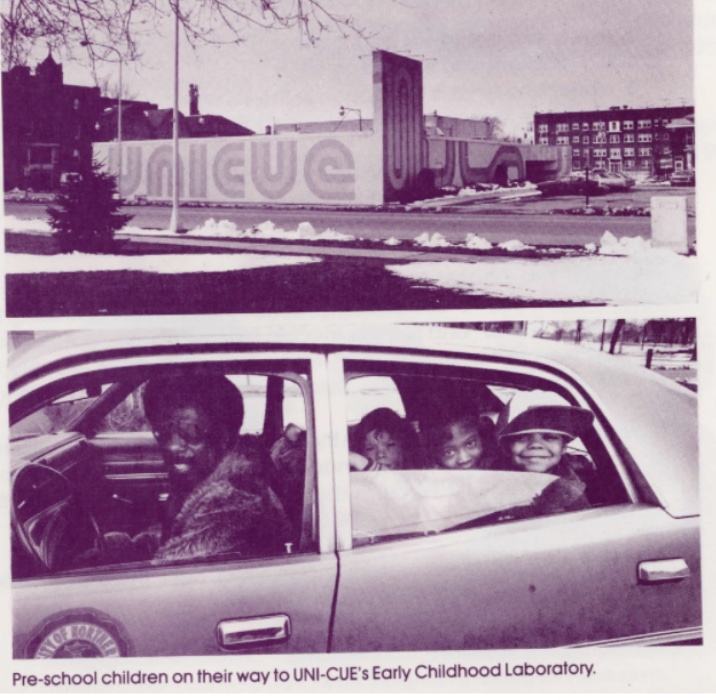

UNI Center for Urban Education Opens

The new building of the UNI Center for Urban Education is dedicated in Waterloo. UNICUE’s mission is to help students in Waterloo to continue their education and to train career readiness. Its focus is specifically on providing educational opportunities for underprivileged and underrepresented members of the Waterloo community.

Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Arrives on Campus

UNI opens its first Delta Sigma Theta sorority chapter for African-American women. This marks the first time that the University is host to a non-white womens’ Greek life organization.

Fannie Lou Hamer Visits Campus

Fannie Lou Hamer (Southern Law Poverty Center) and Mary Berdell (councilwoman, 4th ward) speak on “I’ve Known Struggles: Civil Rights, Past and Present.”

Maya Angelou Visits Campus

Maya Angelou visited campus. She is a noted African-American author, poet, and civil rights activist.